By the release of the second edition of LOTR in 1965, Tolkien was anxious to get his manuscript of The Silmarillion published. The vast majority of Tolkien’s 1965 letters, in varying degrees, are concerned with its ‘completion’ and publication. Remember, that Tolkien had hoped to publish both The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings in the 1950s but post-war paper costs had really made that prospect unfeasable. In January 1966 (Letter # 284 ) Tolkien tells poet and former student W.H. Auden, who had recently been contracted to write a short book about Tolkien, that he wishes it (the short book) could wait until The Silmarillion is published. There is a quiet but distinct desperation growing in Tolkien and we should be attentive. Tolkien knew his legendarium was not complete and was at risk of being wholly misunderstood.

Thus far his foreword to the 2nd edition has chronicled his desire to distance LOTR from its presumed source material, The Hobbit, and connect it more closely to its true source The Silmarillion. Now Tolkien moves on to the business of clarifying the “source” and “meaning” of LOTR.

“ . . . The Lord of the Rings has been read by many people since it finally appeared in print; and I should like to say something here with reference to the many opinions or guesses that I have received or have read concerning the motives and meaning of the tale. …

As for any inner meaning or ‘message’, it has in the intention of the author none. It is neither allegorical nor topical. As the story grew it put down roots (into the past) and threw out unexpected branches; but its main theme was settled from the outset by the inevitable choice of the Ring as the link between it and The Hobbit. The crucial chapter, ‘The Shadow of the Past', is one of the oldest parts of the tale. It was written long before the foreshadow of 1939 had yet become a threat of inevitable disaster, and from that point the story would have developed along essentially the same lines, if that disaster had been averted. Its sources are things long before in mind, or in some cases already written, and little or noting in it was modified by the war that began in 1939 or its sequels.”

We might take a moment to mention the ways in which the contemporary love of “world-building” leads to a misreading of Tolkien. Maps, histories, backstories, and geography are well and good and, indeed, it’s strategy is at the heart of modern fantasy fiction (Terry Pratchett, George R.R. Martin et. al.). This is an incorrect ordering of Tolkien’s process, however, and leads to the wholly destructive habit of mining the legendarium for meaning, pictures, and types. Tolkien’s Legendarium is built up from language (it’s philological) and the tale of LOTR is rooted in that past. Its meaning, like Beowulf, is mythopoeic—it is born from language, poetic beauty, and the truthfulness of myth.

Allegory, literally meaning veiled for figurative language, is a device or style that someone like C.S. Lewis would have been more keen on reviving. Unlike Lewis’ Narnia or Space Trilogy, Tolkien did not build a world to mean something but rather recovered people, places, and events through what we know of their language. People, place, and events just “are”. What does that mean? It means that Tolkien was hoping to shed light on the inner workings of reality rather than give us an invented lens to view or make sense of the reality we see.

Tolkien’s biographer Humphrey Carpenter writes, “Tolkien believed that he was doing more than inventing a story.” (Carpenter 92) Or as Tolkien said, “I had the sense of recording what was already ‘there’, somewhere; not of ‘inventing’”. [note: also see Letter #34 from 1938: “not an allegory”]

What Tolkien want’s us to pay particular attention to, then, is the ‘crucial chapter’ - “The Shadow of the Past”. Considerable time will be spent unlocking the chapter.

SO WHAT?

“The real war does not resemble the legendary war in its process or its conclusion. If it had inspired or directed the development of the legend, then certainly the Ring would have been seized and used against Sauron; he would not have been annihilated but enslaved, and Barad-dûr would not have been destroyed but occupied. Saruman, failing to get possession of the Ring, would in the confusion and treacheries of the time have found in Mordor the missing links in his own researches in Ring-lore, and before long he would have made a Great Ring of his own with which to challenge the self-styled Ruler of Middle-earth. In that conflict both sides would have held hobbits in hatred and contempt: they would not long have survived even as slaves. ”

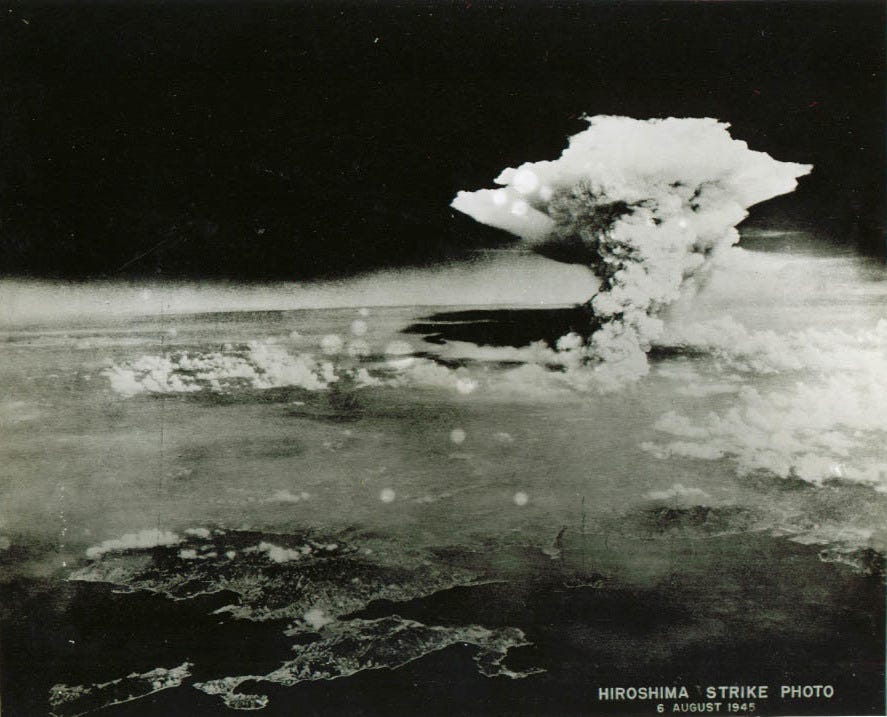

Why is all of this so important? It’s important because though our own age (the Fifth Age of Middle-earth) is a continuation of the great story it is decidedly different. Here we see Tolkien levy a heavy critique, that can be found in great detail in his letters, on what was conceded and lost during WW2. Something has changed in the world since the calamity of WW2 and, as Tolkien notes in his rough calculations of the ages of Middle-earth in Letter #211, that change is accelerating.

By calling LOTR allegory or trying to decipher its meaning [the Ring is the Bomb etc.] leads to saccharine celebrations of our interpretation of the legendarium [something P. Jackon’s films lend themselves to] and, worse, is to miss the disastrous events of our own age. Hence: It’s wholly appropriate and even beneficial to say that the size of Hobbits is irrelevant and are not a celebration of the marginalized and weak - it’s their ordinariness that matters; or Tolkien’s belief that WW2 signaled the collapse of civilization and the rise of “the Machines” not a victory of Liberalism over Fascism. On a whole, Tolkien believed that the end of World War 2 was a Sauronic victory as the paragraph above would indicate. So, the Fifth (or Sixth?) Age of Middle-earth began with the splitting of the atom. This is now commonly called ‘the anthropocene’.

Incidentally, in 1964 (Letter #256 and #338 ) Tolkien reveals that he began and abandoned a “sequel” to LOTR - The New Shadow - where a darkness begins to creep back into a post war Middle-earth bored with peace and enjoyed “playing orc”. Alas . . .

The road goes ever on . . .